Prior to ordination, I didn’t give much thought to the orientation of worship. Versus populum was the presumed posture of nearly every Anglican Eucharist I had ever attended, with a few notable Anglo-Catholic examples. These occasions were sort of fun field trips in my formative stage of converting from Pentecostalism - exotic, arcane, a sometimes-treat. I had certainly never served an east-facing Mass or thought of it as a possibility in my own ministry. It was discussed on occasion in seminary as a vestige of the pre-Reformation that the Church of the future would be unlikely to revisit. The attitudinal vibe was that east-facing Eucharist was a precious, ritualist indulgence and that we who bask in the light of the Second Vatican Council would not be turning our backs to the congregation again any time soon. Then, the option was presented to me in the form of my first and current appointment.

In one of the two parishes I serve, I have the rare gift of a wall-mounted, east-facing high altar. The practice of this particular parish, like many who are still in possession of fixed altars that can’t come off the eastern wall, has been to use a nave altar fitted with casters for most worship services. To my knowledge, use of the high altar had been reserved for Easter Sunday at the time of my appointment. I felt intimidated by the whole conversation about posture, particularly having been appointed and serving in the parish prior to ordination. I saw the value of having both orientations of prayer available in my liturgical tool belt and recognized where I felt the outer reaches of my comfort zone being stretched. We now use the high altar on principal feasts and the occasional weekday festal service.

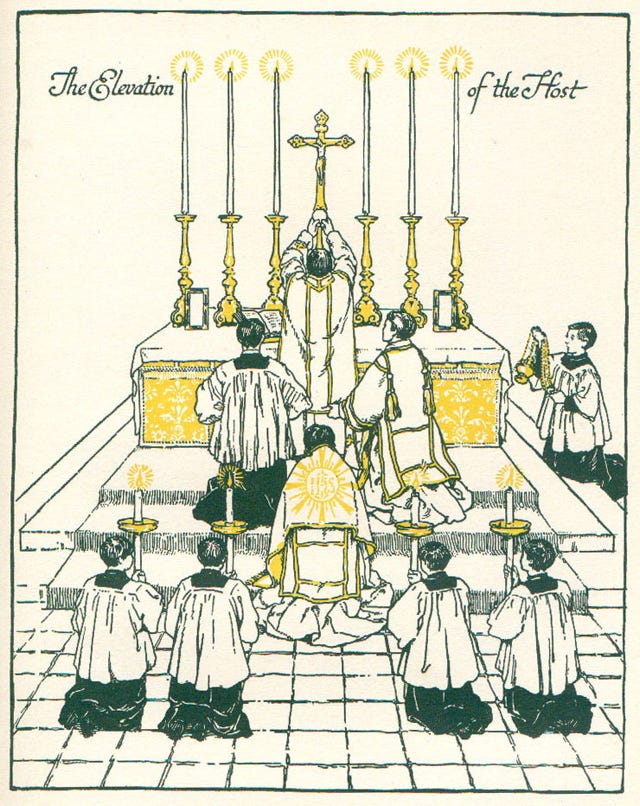

I can’t remember on which feast I first celebrated Mass ad orientem. But I do remember how it felt. Hearing the voices of the congregation behind me in the pews, suspended and upheld by their silent prayers as I offered the Great Thanksgiving, gazing upward to heaven while elevating the host and chalice, I was being drawn deeper into the Eucharistic mystery and my sense of it. I say sense rather than understanding because the more I contemplate the Eucharist, the less I grasp rationally and more I intuit its truth and beauty. Another notable occasion was an Ascension Day BCP service, where I preached about significance of Christ ascending into heaven fully human and fully divine, and the implications of a piece of humanity dwelling at the right hand of the Father. After a few other occasions of celebrating at the high altar, the spiritual appeal and wisdom of the east-facing Mass was crystallized when I attended an Anglo-Catholic parish on its patronal feast this summer. Not as a sacred minister, as a member of the congregation. There was something exceptional about that particular Mass, and as I closed my eyes during the offertory motet - an astounding piece of polyphonic chant - I felt us all, congregation, sacred ministers, the communion of the saints, being raised up into the presence of God. Oh, I thought, that’s why this matters.

The intentional use of the body is one of the most attractive features of Anglican liturgy. Controlled, effortful, planned movement as part of worship is what grounds our concentration and attention to what is taking place before us. One of the greatest adjustments in my liturgical thinking through vocational formation is that the movement that we employ has theological underpinning. Of course which side of the altar the priest stands on matters. It’s got to be more than a question of practicality, or fondness for tradition, or rejection of the same.

A short way into the Advent season, I’ve been contemplating the orientation of worship and its relationship to the kalendar. Although, based on my track record, I’m seldom not considering the kalendar. The Mass versus populum accentuates the nature of the Incarnation, of Christ entering the immediacy of the human condition, and the inclusion of laity. It is Jesus being made truly present in the context of the community, coming to dwell with us in the place where He promised to do so. A congregationally-oriented Eucharist is communitarian, pastoral, and anchored in the comfort of the Incarnation. Emmanuel is here. How perfectly complementary for the season of Advent.

The same could be said for an east-facing celebration. Turning ourselves and looking to the East, to the direction from which our salvation comes (both in the historical reality of Christ’s birth and the prayed-for eschaton), is appealing in its own way. No, the laity can’t see exactly what’s happening with the priest’s manual actions and perhaps the words of the Mass are difficult to make out, but the Eucharist is not a performance and the apotheosis of participation is not everyone doing the same thing at the same time. The roles of sacred minister and lay person may be more defined in this postural arrangement, but they mustn’t be thought of as totally severed because the celebrant “has their back turned”. In Mass ad orientem, the movement of activity is also communal. In it, we are looking East together, focusing on the Sacrament together, directing our spoken and silent prayers toward the source of our hope together. In this arrangement, the margins for distraction or overemphasis on the priest’s affect/trembling hands/charisma at the table are reduced. It is a reminder that salvation comes to us from outside of ourselves, our world, our perception of reality, while giving us a fixed point to steady our perspective and invest our hope. Raise up your heads, your redemption is drawing near.

All liturgical decisions should have prayerful intention behind them, including and particularly the use of the body in space. Celebrating ad orientem isn’t going to be ideal for every parish or cleric, but we mustn’t banish it from Anglican liturgy wholesale. Turning East has just as much spiritual merit and legitimacy as normatively facing West, and in this very ancient practice there may be beauty, revelation of the Divine presence, and transcendence. In the season of Advent, where our attention is drawn to the anticipation of Christ’s First and Second Coming, on those more mystical feasts where our attention is drawn heavenward, and any time in which we need to step away from the burdens of the world and glimpse the promises of God’s Kingdom, made manifest in the Real Presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

People, look East! and sing today: Love the Lord is on the way.

To end, a poem. Not by me.

“What I like about being a priest is nothing to do with cultic beast

or having a message to write on the leaves

or offering charms to the heart that grieves

or counting the sheep in a pitch-pine fold

or wearing a shirt of cloth-of-gold,

no, none of these - but marrying the glory to the little thing:

to eavesdrop on a monologue delivered to a woolly dog;

to hear the tones of righteous rage excite the prophet of school boy age;

to sit down in a bus behind four lots of fingers intertwined;

to see the boy’s face in the man’s blush when he comes to put up the banns:

to watch rheumatic ladies pat a blessing on a pampered cat -

what I like about being a priest is turning everything to the east.”

“Knotty Nineties” by Hilary Greenwood